The Name of the Rose is a fabulous book and film about monks, books, murders and the multiplicity of signs and meanings. I just re-read the book over this last week (finally found a nice early hardcover edition that was cheap ...) Of course, purists will argue that the film doesn't manage to get down complex themes involving the language, production, ownership, authority, history, and philosophy of language. But, it still holds a special palce in my heart. Here are a few of my favorite images from the film.

I like this shot because it floods the screen with light and still manages to bisect the lower half of the frame with the gaping blankness of the stairwell. I think it captures that transition into the esoteric world of scholarship very nicely.

I like this shot because it floods the screen with light and still manages to bisect the lower half of the frame with the gaping blankness of the stairwell. I think it captures that transition into the esoteric world of scholarship very nicely.

Another great shot, blurred around the edges because it's supposed to be seen through a primitive pair of specs that William of Baskerville owns. I suppose it would be a strange world where donkeys preach to bishops, but then again, perhaps the self-contained hyper-rationalism of late-industrial capitalism can only be countered by fantasies such as these.

Another shot of an illuminated manuscript. They actually got monks who restore books to paint these pages for the film. Apparently this page went missing after they started the shoot (one of film's producers liked it and just TOOK it without realizing that its importance to the scene). It then took several months for the page to be re-produced and the rest of the scene had to be re-shot on the eve of wrapping up the production (The producer was very embarrassed when it all came out ...)

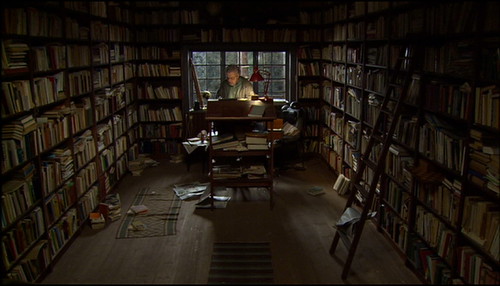

"Adso, do you realize that we are in one of the greatest libraries in all of Christendom?"

I identify a lot with this attainment of the secret library because I've spent the last two years sneaking around Columbia's library (yes, I don't go there but they've got lots of great stuff ...).

The obligatory "burn-the-heretic" scene. That's Ron Perlman as Salvatore, the former heretic who speaks all languagees but none. I'll admit that there was a time (quite long ago) when I was so into the film (which I had managed to record off Channel 5 ...) that I could sing the strange chant that Salvatore sings at this moment. Eeeks.

The obligatory "burn-the-heretic" scene. That's Ron Perlman as Salvatore, the former heretic who speaks all languagees but none. I'll admit that there was a time (quite long ago) when I was so into the film (which I had managed to record off Channel 5 ...) that I could sing the strange chant that Salvatore sings at this moment. Eeeks.

Finally, William gets his hands on the Book! When I first saw the film on TV, I was so entranced by it that I went out to get the book from the NLB. I was supposed to have been studying for a Sec 3 Lit exam (on Macbeth, actually). I ended up doing really badly on that exam. It did steel my resolve, however, to conquer "O" level Lit (even if it meant memorizing the entire play, since that seemed to be the only thing that Lit teachers gave credit for back then). Ah well.

Finally, William gets his hands on the Book! When I first saw the film on TV, I was so entranced by it that I went out to get the book from the NLB. I was supposed to have been studying for a Sec 3 Lit exam (on Macbeth, actually). I ended up doing really badly on that exam. It did steel my resolve, however, to conquer "O" level Lit (even if it meant memorizing the entire play, since that seemed to be the only thing that Lit teachers gave credit for back then). Ah well.

I like this shot because it floods the screen with light and still manages to bisect the lower half of the frame with the gaping blankness of the stairwell. I think it captures that transition into the esoteric world of scholarship very nicely.

I like this shot because it floods the screen with light and still manages to bisect the lower half of the frame with the gaping blankness of the stairwell. I think it captures that transition into the esoteric world of scholarship very nicely.

Another great shot, blurred around the edges because it's supposed to be seen through a primitive pair of specs that William of Baskerville owns. I suppose it would be a strange world where donkeys preach to bishops, but then again, perhaps the self-contained hyper-rationalism of late-industrial capitalism can only be countered by fantasies such as these.

Another shot of an illuminated manuscript. They actually got monks who restore books to paint these pages for the film. Apparently this page went missing after they started the shoot (one of film's producers liked it and just TOOK it without realizing that its importance to the scene). It then took several months for the page to be re-produced and the rest of the scene had to be re-shot on the eve of wrapping up the production (The producer was very embarrassed when it all came out ...)

"Adso, do you realize that we are in one of the greatest libraries in all of Christendom?"

I identify a lot with this attainment of the secret library because I've spent the last two years sneaking around Columbia's library (yes, I don't go there but they've got lots of great stuff ...).

The obligatory "burn-the-heretic" scene. That's Ron Perlman as Salvatore, the former heretic who speaks all languagees but none. I'll admit that there was a time (quite long ago) when I was so into the film (which I had managed to record off Channel 5 ...) that I could sing the strange chant that Salvatore sings at this moment. Eeeks.

The obligatory "burn-the-heretic" scene. That's Ron Perlman as Salvatore, the former heretic who speaks all languagees but none. I'll admit that there was a time (quite long ago) when I was so into the film (which I had managed to record off Channel 5 ...) that I could sing the strange chant that Salvatore sings at this moment. Eeeks. Finally, William gets his hands on the Book! When I first saw the film on TV, I was so entranced by it that I went out to get the book from the NLB. I was supposed to have been studying for a Sec 3 Lit exam (on Macbeth, actually). I ended up doing really badly on that exam. It did steel my resolve, however, to conquer "O" level Lit (even if it meant memorizing the entire play, since that seemed to be the only thing that Lit teachers gave credit for back then). Ah well.

Finally, William gets his hands on the Book! When I first saw the film on TV, I was so entranced by it that I went out to get the book from the NLB. I was supposed to have been studying for a Sec 3 Lit exam (on Macbeth, actually). I ended up doing really badly on that exam. It did steel my resolve, however, to conquer "O" level Lit (even if it meant memorizing the entire play, since that seemed to be the only thing that Lit teachers gave credit for back then). Ah well. The Namesake. Jhumpa Lahiri. This came in the mail yesterday (second-hand book buying is one of the best reasons of living here) and after some late night reading and a final burst this morning, I'm left tingling by the uncanny emotional resonance that tied me to the novel. It's not the immediately spottable New York references that struck a chord (those were fun, but on the level of spotting places from movie sets or on TV that you just wandered past the day before .... ). It was the strange journey that its protagonist takes to a place thousands of miles away, in order to be someone else; a journey which now so many take, that left the sense that our myths no longer map the epic, tragic and comic journeys home of Odysseus, Oedipus and Frodo; neither do they follow the aimless wanderings of Don Quixote or Dean Moriarty. Instead, they trace the unsettling attempts to find the self on distant shores. Amazingly well written, and though it goes flat in the middle (with cliched descriptions of yuppies in New York ... eeks ... ), it ends powerful.

The Namesake. Jhumpa Lahiri. This came in the mail yesterday (second-hand book buying is one of the best reasons of living here) and after some late night reading and a final burst this morning, I'm left tingling by the uncanny emotional resonance that tied me to the novel. It's not the immediately spottable New York references that struck a chord (those were fun, but on the level of spotting places from movie sets or on TV that you just wandered past the day before .... ). It was the strange journey that its protagonist takes to a place thousands of miles away, in order to be someone else; a journey which now so many take, that left the sense that our myths no longer map the epic, tragic and comic journeys home of Odysseus, Oedipus and Frodo; neither do they follow the aimless wanderings of Don Quixote or Dean Moriarty. Instead, they trace the unsettling attempts to find the self on distant shores. Amazingly well written, and though it goes flat in the middle (with cliched descriptions of yuppies in New York ... eeks ... ), it ends powerful.